Man Ray Chess Set

The Dada and Surrealist artist Man Ray (1890–1976) designed several iconic chess sets throughout his career—most notably a 1926 version now held in the MoMA collection, and a 1945 edition once owned by David Bowie. These geometric, sculptural pieces blurred the line between art object and functional game.

This project revisits that legacy through a modern lens: a functional replica that merges elements of Man Ray’s historic designs, recreated using 3D modeling, silicone mold making, resin cold casting, and custom finishing. The result is both homage and experiment: an exploration of how contemporary fabrication techniques can reanimate avant-garde design nearly a century later.

The Art of Play

A chess set only fulfills its purpose when it is used. Man Ray’s pieces, though sculptural, were never meant to remain untouched, with their meaning unfolding through movement across the board. Play transforms abstract forms into strategy, tension, and surprise. This was part of the avant-garde vision: to collapse the distinction between art object and lived experience. Each game is a performance where design meets decision, reminding us that while art can be serious, it can also playful, social, and unpredictable.

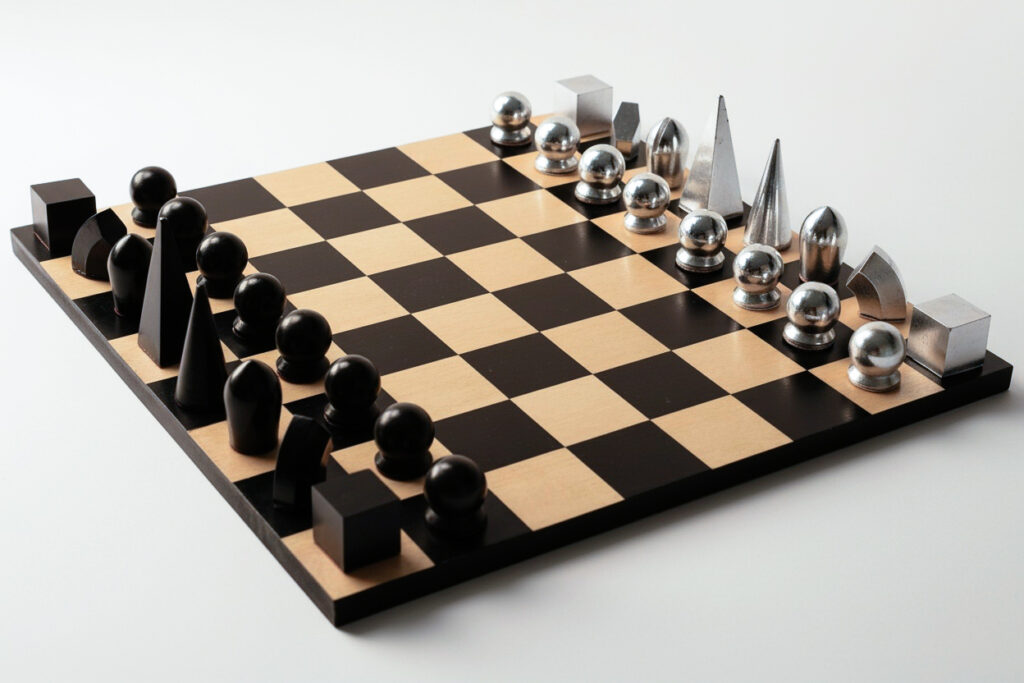

The Art of Art

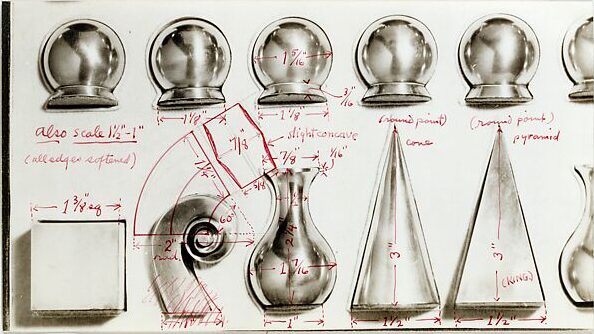

When Man Ray designed his chess set in 1924, he treated each piece as an abstract sculpture. Instead of mimicking crowns, bishops, or knights, the forms reference Euclidean solids: the pyramid, sphere, and cone. This approach was consistent with his work in the Dada and Surrealist movements, where function and absurdity often overlapped. Like Duchamp—himself a serious chess player—Man Ray saw the game as a site where art could intervene in everyday life. The chess set therefore belongs not only to the history of design, but to the avant-garde project of collapsing boundaries between art and play. The Silver/Black Edition here recalls this emphasis by heightening contrast, turning the set into a study in form and shadow.

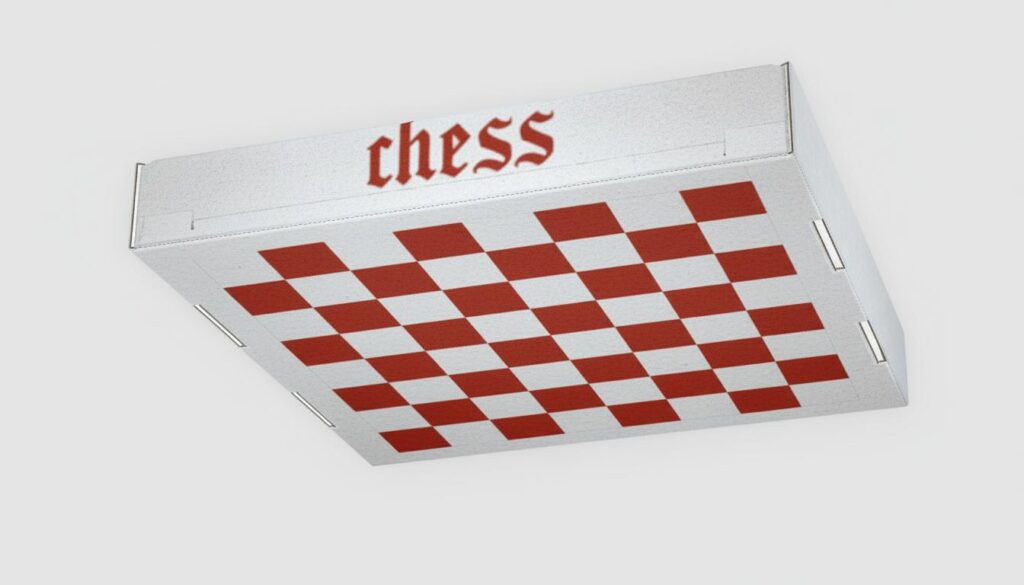

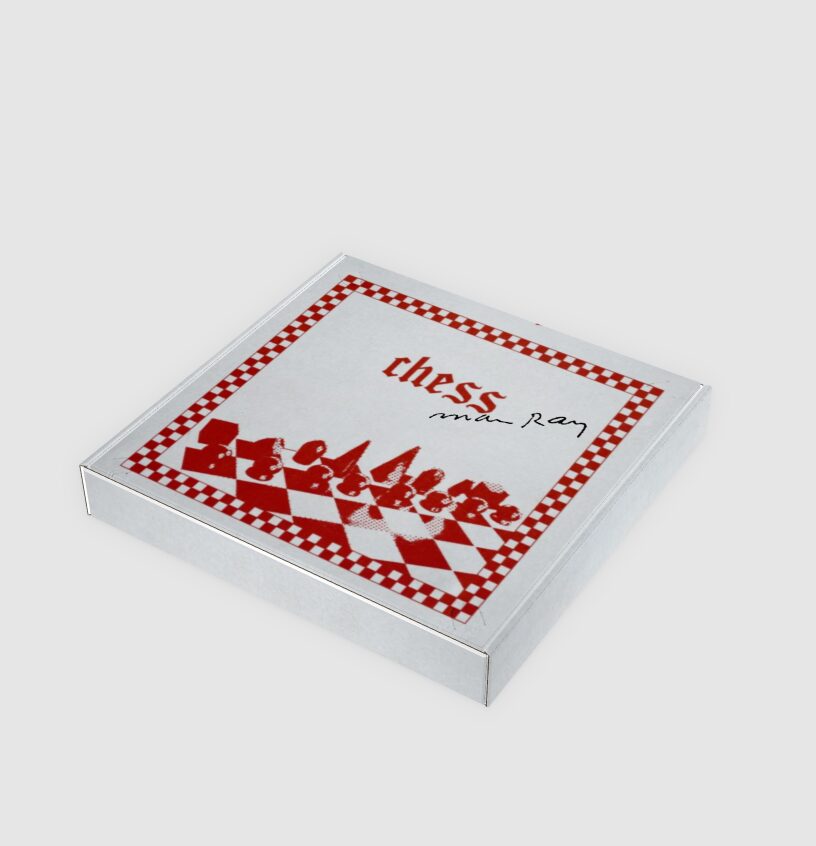

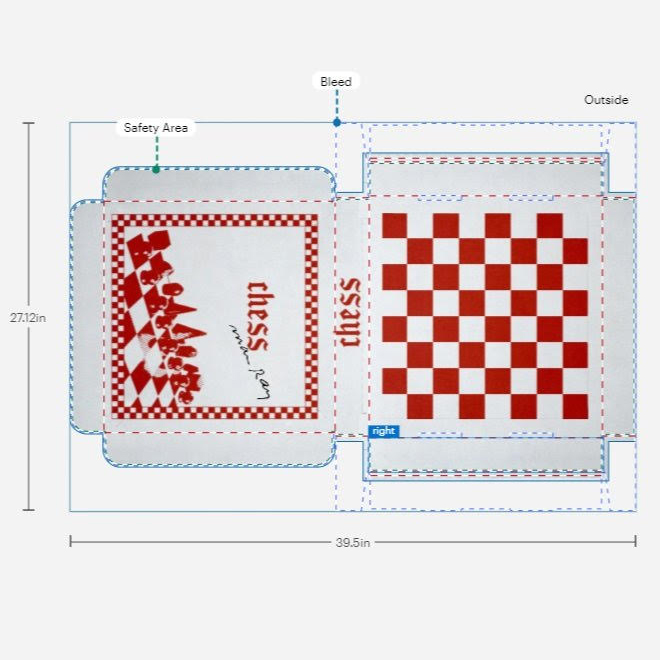

The Art of Packaging

Packaging has always been more than decoration. It solves problems. A good container must protect fragile pieces, keep them organized, and present them clearly for use. Modernist designers in the 20th century treated those same challenges as opportunities, making packaging part of the design language itself. The Takeout Case is our way of placing the set in that lineage and extending its playfulness. Its presentation also echoes something more familiar: the flat, square proportions of a pizza box. The Red/White Edition leans into that comparison, bold and graphic, reminding us that packaging doesn’t just store an object, but frames how we first encounter and remember it.

The Art of Photography

Photography was central to Man Ray’s artistic identity. His “rayographs” and experiments with light and shadow helped redefine the medium in the 1920s. Applying this photographic lens to the chess set highlights how light activates the pieces, casting geometric forms into relief and turning the game into a sequence of images. In broader art history, this echoes the dialogue between object and representation—between the crafted form and the photograph that circulates it. To study the set through photography is to continue Man Ray’s project: collapsing the boundaries between object, document, and art.

The Crystal Edition makes this dialogue especially visible: refractions animate the forms, allowing photography to become not just a method of documentation but a continuation of the artwork, exploring where object ends and representation begins.

The Shape of Play

Man Ray approached chess the same way he approached art: by stripping objects down to their most essential forms. Inspired by Marcel Duchamp, a close friend and fellow Surrealist who was deeply devoted to the game, Man Ray began designing chess sets in the 1920s. Like Duchamp’s “readymades,” his pieces were modeled from everyday geometric forms found in his studio: a pyramid for the king, a cone for the queen, vases for bishops, cubes for rooks, spheres for pawns, and a violin scroll for knights. These designs blurred utility and sculpture, turning the familiar game into a field for experimentation and play—all despite calling himself nothing more than “a third-rate player.”

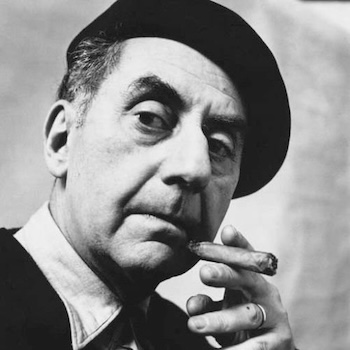

The “Man” behind the Set

Man Ray (1890–1976) was an American artist central to the Dada and Surrealist movements. Renowned for his experimental photography, film, and sculptural objects, he consistently reimagined ordinary forms through a conceptual lens. His chess sets, designed between the 1920s and 1940s, exemplify this approach, transforming geometric simplicity into playful and enduring works of art.